A Conversation about documenta fifteen Kassel, june 18 – september 25. Artistic direction/curator: ruangrupa

The End of Exhibiting as We Know it

This summer, artists and curators, Ruth Aitken and James Lee, explored the buildings and parks of Kassel, Germany, full of art for the duration of the documenta fifteen – the extensive exhibition taking over the city, every five years. In this discussion between the two, they share their reflections on some of the material-based art presented at the latest edition, communality, controversies, and documenta’s problematic use of the term “sustainability”.

This edition of documenta features about 1500 contributing artists; the exact number is not even known to the organisers, such is both the scale and the method that the exhibition has been curated this year. Indonesian artist collective ruangrupa, were invited to organise and curate this year's edition. In turn, ruangrupa invited 14 other collectives to help them curate and exhibit as part of the festival who – again, in turn – extended invitations outwards to other (mainly) collectives to contribute to this documenta. This edition has not been short of controversy either. A central controversy this year has been around antisemitism. This was initially around the inclusion of supporters of the BDS movement ‘(Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions’ in relation to Israel and products from Israel is a protest against the ongoing occupation of Palestinian land, is seen as antisemitic in Germany[1]), and involved a break-in to one of the exhibits. It escalated with the discovery of an anti-semitic image in a centrally placed mural by the Indonesian art group Taring Padi. The controversy escalated to the point where the artwork was removed, the Director General of documenta was forced to resign and the German Cultural Ministry – funders of documenta – demanded an investigation into how something like this came to be included in the first place, with the supervisory board of documenta initiating a process of investigation into artworks on show for possible further antisemitic content.

By the time we reached Kassel, the offending artwork had been removed, and one could walk around virtually oblivious to all that had happened in relation to this unfolding drama. As of the end of July 2022, many of the collectives involved had sent an open letter to the documenta board titled Censorship Must be Refused: A Letter from lumbung community. It demands, amongst other things, “that the recommendation to hire a board of scholars to review the artworks is immediately retracted” and that various other forms of harassment or discrimination experienced by participants in the festival are properly investigated and “that the offenders and perpetrators of the recorded offenses thus far are held accountable by documenta and the city of Kassel”. What this “accountability” could mean is not spelled out in the letter. The situation is dynamic and changing and whether we get to a situation whereby artists or further artworks are withdrawn, either by the artists in protest, or for their content by documenta, is uncertain.

RUTH: We have been traveling back to Norway from the UK by train, via Kassel, and the overriding sensation is, not of an empire in decline but one already over and ultimately unaware of its fall. documenta 15 adds to this feeling. The day before we arrived in Kassel there had been wildfires on the city's peripheries. Going around documenta itself –particularly the main exhibition space, the Fridericianum building – was a physically uncomfortable affair, with notes on doors reminding you to keep them closed to aid trapping cool air in the packed, neoclassical building. Alongside the unparalleled heatwave across Europe, there are workers striking and massive staff shortages across different segments of European industry.

JAMES: I would say it is a tad hyperbolic to talk of much of Europe as ‘over’. The Germans are notorious for underinvesting in their public services, likewise the English; so no wonder getting to Kassel from the UK via train was chaotic for us (trains repeatedly cancelled, a mess of different service providers with tickets not valid on different services, overcrowding, massive delays, etc.).

This also brings us to our first topic of conversation though, sustainability. One is very much aware of the issue of climate change not always through the content of the show but with all that was going on in the world at the time we experienced documenta. As you mentioned, forest fires and record-breaking temperatures recorded in Europe – and us being very, very hot as we wandered around these public parks in Kassel.

RUTH: There is an irony in the statement of sustainability from documenta, particularly in relation to the work of the artists and collectives; so much has been considered and seems to have been actively worked through within the groups themselves. For example, there is an artwork by Nest Collective talking about the knock-on impacts, both environmentally and economically, to East Africa of a throwaway, ‘fast fashion’ based western textile industry.

They have built a structure, Return to Sender, which housed a cinema space, made from bales of second-hand textiles. Inside played a film discussing the flooding of East Africa with second-hand textiles from the USA, Canada and Europe, often in such a terrible condition that they must go to landfill in the countries that receive them. The film also discusses how this hinders or crushes regional clothing industries, resulting in a lack of economic growth and a lack of “personal dignity” (as it was put by one talking head in the film); a population only allowed, through circumstance, to wear the tired leftovers of the West, with little room for personal or cultural expression.

This is in contrast to the documenta shop, where one can buy branded documenta T-shirts which suggests the pressures of commerce rubbing up against a curatorial message. The sustainability statement by documenta says a lot about learning how to mitigate environmental impacts, but very little about how they are actually doing it.

JAMES: I would say that to talk of environmental sustainability in an event like this one, is obviously difficult: can an exhibition that is supposed to show art from around the world in one place, ever be truly environmentally responsible? The curatorial model adopted for this edition seems terrible for keeping carbon emissions to a minimum as well: thousands of participating artists and art works, all needing to be flown or shipped in. And that is before we begin to talk about the hundreds of thousands of tourists making their way to view the exhibition, all of whom will need to be fed and sheltered. But is the goal noble or utopian enough that it circumvents the imperative to keep carbon footprints as low as possible?

RUTH: I think there is a very valid question about the sustainability of these old industrial models of art (the ever-increasing number of internationally focused biennials), which the environmental, climate and pandemic crises have brought to the fore. However, in the present, I do not feel that any arts organisation – particularly one of the largest in Europe – should still be searching around, unsure of what the immediate solutions are. Nor should their manifesto be to “ensure the topic of sustainability is similarly brought to the attention of documenta fifteen visitors”, without also discussing real time solutions – i.e we advise those who can to travel by public transport, we advise those who would need to fly to consider whether they need to be here in person or can join via online events, we offer all artists traveling here the opportunity to travel by land where possible and offer them a per diem for the additional travel time etc.

Moving past sustainability as a topic, I would like to pick up on the other themes in Nest Collective’s work, the idea of both cultural and personal dignity. I feel we must mention a standout series of works by Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Out of Egypt, displayed in the Fridericianum. The works are a loving reclamation of her own culture and identity. Reusing textiles belonging to those she is portraying, she reimagines the 17th century etchings of Jacques Callot, a French printmaker, who depicted and perpetuated stereotypes of Roma life.

JAMES: I think we can both say we were super impressed by Małgorzata Mirga-Tas and her textile collages. I liked the way these works blurred the lines between abstraction and representation, between craft and fine art. Various textiles were used to block out shapes in the image and these shapes would form a person or build a background. A blue fabric would be used to represent a sea; a golden colour was used for a beach. Flowers would be represented by an old curtain which had a flower pattern printed on it. It was so nice to see such a simple idea being done well. A lot of colour, a lot of joy, and a lot of inventive visual techniques, which, in the context of this documenta, reminded me of the power of more traditional forms of making in an exhibition dominated by the social and the relational.

This practice of Migra-Tas fits nicely into a trend of contemporary art over the last decade, the resurgence of craft. But in general, I suppose documenta is always a way to see which trends are still going strong and what trends are dying in contemporary art. A trend which I thought was dying, but is out in force here, is the use of archives and the “archive exhibition”.

The Fridericianum has largely given over its most prominent spaces to the presentation of archives of various kinds. These archives are not necessarily even ‘art’ archives i.e. about an artist, or from an artist's estate, but rather about something ‘not art’ at all. The most obvious example, in my opinion, would be the archives of the feminist-led protest movements in Algeria from the 1980s, compiled by various scholars.

Another trend, that has been brewing in the last five years or so, is the presentation of ‘not art’ in art spaces, meaning the line between what is art and something else (an archive of interesting things, a community project, a nightclub, a garden) will get presented in these art spaces, really confusing the line between ‘Art’ and ‘Not Art’. Obviously, one could say this is not unique in the western art world. For example, this is not too dissimilar to relational practices of the 1990s; here we have projects coming from the other direction, being placed on a pedestal by the art world as being deemed to have ‘worth’ not related to aesthetics, but to politics and values.

Good examples of this in this documenta would be the nightclub space by Party Office and the garden and eating space by Britto Arts Trust outside of documenta Halle. My pitch to curate for the next documenta would be to just present lots of interesting projects that have nothing to do with art but about building and maintaining communality – taking the thesis of this exhibition to its logical conclusion.

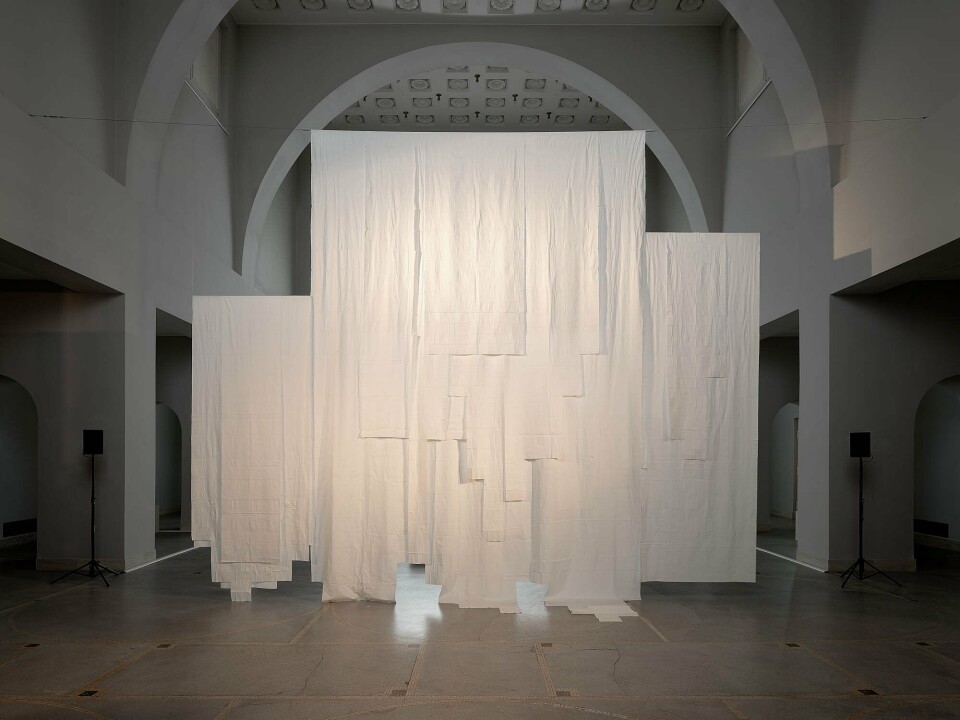

RUTH: I disagree. Britto Arts Trust is explicitly an arts organisation. Nor would I suggest that any of the art suffers due to a more complex understanding of what art is. I have read quite a few reviews that bemoan the lack of ‘beauty’ and ‘art’, which I just do not think is played out in the festival, even in the fraction we saw. There are many moments of real beauty – I would particularly point to the monumental white hanging work Aşît, which sat alongside a film of the same name by Pınar Öğrenci in Hessisches Landesmuseum. In collaboration with Öğrenci, women who have suffered from armed conflict in Van, in Turkish Kurdistan, produced the work from stitched together tissue serviettes, vast and light and fragile, creating a barrier between the public and the film, and seemingly dancing between realms.

It just seems that art for art's sake is no longer a singular intention. Many of the collectives/artists disregard this (perhaps dated) idea, combining aesthetic inquiry into practices oriented towards living, not segregating the aesthetic realm to the gallery, but regarding it an inseparable part of the everyday. This means it will always be political. With many of these collectives, within that political engagement there is a use of aesthetics and objects to not just discuss but actively shape the material conditions that people are living under, and vice versa – changing the material conditions people live under to enhance the aesthetic and spiritual condition. In this regard, I think of the Party Office with their manifesto advocating for ‘radical pleasure’ within a sensorial night club dedicated to just that. Outside of documenta Halle, Britto Arts Trust' have a garden palan and kitchen pak ghor, and inside they have a bazar/shop front rasad filled with ceramic, metal and crocheted food products melded with an assortment of other foods, with weaponry or stamped with corporate branding, pointing (quite unsubtly) to the intense interventions of vying corporate, governmental and geopolitical forces within our food system. This is directly contrasted with the collaborative, collective kitchen outside where they are planting, feeding, building communities and conversations, and blending the social, political, material, aesthetic and spiritual into a complex and affirmative soup.

I do however agree; I wish documenta had gone further. The parts that work best are the areas where chaos is allowed to reign, ideas and objects are colliding with one another, and there is no aim to contain it within an art ‘order’.

JAMES: To bring our conversation to a conclusion, I think that – for the most part – my disappointment was with the display rather than the art. Basically, there is too much stuff in too small a space in the main exhibition halls. I suppose this is what happens when one invites 1000-plus artists to exhibit. However, as soon as one got out of these bigger spaces and into the smaller spaces, the exhibits suddenly had space to breathe.

One of the most impressive discoveries for me in this documenta was a group called El Warcha from Tunisia. Their space doubled as a karaoke bar by night, but – maybe because they are architects dealing with space and how people move and engage with spaces as a profession – their space was not dead as an exhibition space during the day. One could get an overview of their practice on a TV (mounted in an area that would become a stage for the karaoke singer later). The TV played a 70 minute documentary summing up their practice, almost a video C.V – but, you know, actually good. Their practice overall was inventive, relying on the re-use of old materials and cable ties to hold it all together.

R & J: documenta 15 is an exhibition which, as a visitor, you can only really scratch the surface of. As the controversies have shown, not even the organisers have an overview or experience of it in its totality. Perhaps it will be best understood by the participating artists who are present, and those locals who can afford a season ticket. As an exhibition, it has a lot to say about the future of art, making visible collectivist attempts to exist outside of the market, and to live one's communitarian values. Its political radicality is ultimately in the creation of space for these artists and collectives to meet, collaborate, and learn from one another; to create a network of artists collectives that can stand in union, which can revolt – for good or for ill – that is maybe not so dependent or easily knocked by the politicking of government funders or the donor class.

Notes

1: See Nasr, Joseph. Germany designates BDS Israel boycott movement as anti-Semitic. Available from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-bds-israel-idUSKCN1SN204